Swiss corporate diplomacy is rewriting the tariff playbook

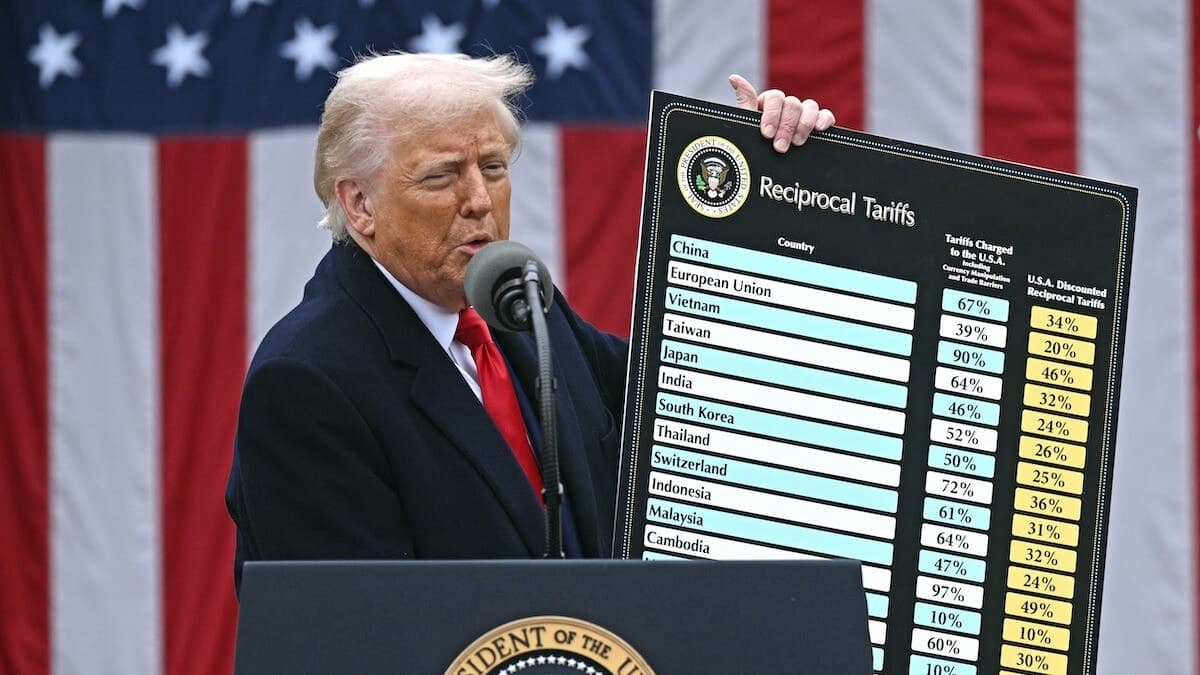

When leading Swiss executives travelled to Washington this month to make their case directly to U.S. officials, they were not lobbying for a niche exemption or a sector-specific reprieve. They were stepping into a space traditionally reserved for governments: diplomacy. Their goal was to soften the 39 percent tariff shock that has unsettled Swiss exporters since the summer. Their method was to tie tariff relief to concrete investment commitments in the United States.

The result could soon be a significant policy shift. According to Bloomberg and Le Temps, Switzerland is on the verge of securing a deal that would bring U.S. tariffs on Swiss goods down to around 15 percent, aligning them with European Union levels. Whether that final announcement arrives in weeks or months, the episode already offers a glimpse into a changing model of international economic engagement, one where companies act as diplomatic protagonists rather than simply the subjects of trade policy.

A new kind of outreach

The speed and visibility of the Swiss corporate outreach surprised many observers. Executives from firms such as Richemont, MSC Mediterranean Shipping Company, ROLEX, Partners Group, Mercuria, and MKS PAMP met senior U.S. officials and even the President to make the case for a recalibration of tariffs. Their pitch went beyond simple protest: they promised to deepen investment and job creation in the U.S. in return for fairer treatment at the border.

In doing so, they changed the tone of the conversation. Rather than presenting Switzerland as a small and aggrieved exporter, they reframed it as a strategic investor in America’s own economic agenda. This was advocacy built on reciprocity, a “give to get” model that resonates with a White House increasingly focused on industrial policy and domestic employment.

For Bern, which had expressed “great regret” over the tariffs but had limited leverage in the negotiations, this parallel track of engagement provided a useful complement. It allowed the Swiss government to maintain a formally neutral posture while letting business leaders explore pragmatic avenues for de-escalation.

Why the private sector took the lead

There are structural reasons why corporate Switzerland found itself at the forefront.

First, the stakes are unusually concentrated. The United States is Switzerland’s second-largest export market, and the sectors most exposed – luxury watches, precision instruments, machinery, and niche manufacturing – cannot simply absorb a 39 percent duty. Each week of delay directly affects profit margins and investor sentiment.

Second, Switzerland negotiates from an asymmetrical position. Without the collective leverage of a large trading bloc, its influence depends on credibility, consistency, and the soft power of its brands. By mobilising their balance sheets and U.S. employment contributions, companies effectively lent the state new leverage that it could not command on its own.

Third, the broader geopolitical backdrop matters. Bern faces growing pressure from both Washington and Brussels to align more closely with Western sanctions on China and to tighten foreign investment screening. Against that backdrop, direct corporate engagement helps depoliticise the immediate tariff dispute and shifts the narrative toward economics rather than geopolitics.

Implications for corporate affairs

For practitioners in corporate affairs, the Swiss episode is more than a case study. It is a signal of where global business diplomacy is heading.

It shows that companies can no longer rely solely on government-to-government channels when trade friction threatens their operating model. In a world where tariffs are used as political tools, credibility comes from demonstrating tangible contributions to the counterpart’s economy. The Swiss firms understood that and acted accordingly.

But this activism also carries risk. When businesses act as quasi-diplomatic actors, message discipline becomes paramount. A misstep or the perception of a divided front between corporate voices and the federal administration can undermine national negotiating power or invite scrutiny at home.

The emerging best practice is coordination rather than substitution: maintain alignment with government ministries, share intelligence, and ensure that every public statement reinforces official diplomacy instead of competing with it.

What happens next

If the reported 15 percent tariff deal is finalised, it will provide immediate relief and restore parity with the European Union. It will also set a precedent. Other small economies may take note, seeing that credible corporate engagement, when aligned with national objectives, can influence U.S. trade outcomes.

Still, the story is unfinished. Any tariff revision could be accompanied by expectations on Switzerland’s stance toward China or its participation in Western supply-chain alliances. Corporate leaders who have taken the initiative must be prepared for the diplomatic complexity that follows success.

A broader lesson

What stands out in this episode is not just the possibility of a tariff cut, but the recalibration of roles. Swiss companies have shown that in an age of economic nationalism, influence increasingly belongs to those who can bridge the worlds of business and policy.

For corporate affairs professionals, the takeaway is clear: trade policy is part of the reputation and risk portfolio. Firms that anticipate its political dimension and can articulate their strategic value in the language of policymakers will be better positioned to protect their interests and contribute to national resilience.

Switzerland’s outreach to Washington may ultimately reduce tariffs, but its deeper legacy lies elsewhere. It demonstrates that, in today’s fractured global order, the line between diplomacy and corporate strategy is no longer a border. It is a shared space.